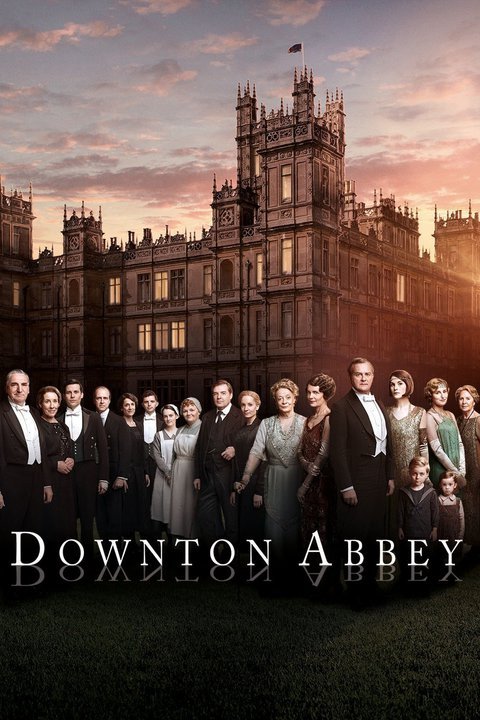

Downton Abbey is phenomenon. A dazzling remake of Upstairs, Downstairs (1971--75), which was arguably better as a drama (well worth a second viewing), but which lacked Downton's docudrama cache and the breathtaking sets. Both series revisit the British empire at its peak, in the early 20th century, when the Union Jack covered half the globe, and the ruling elite lived a high life that can never be matched, no matter how many millions you may have. Genuine fairytale realities, heaven on earth -- at least for the elite.

Downton Abbey is phenomenon. A dazzling remake of Upstairs, Downstairs (1971--75), which was arguably better as a drama (well worth a second viewing), but which lacked Downton's docudrama cache and the breathtaking sets. Both series revisit the British empire at its peak, in the early 20th century, when the Union Jack covered half the globe, and the ruling elite lived a high life that can never be matched, no matter how many millions you may have. Genuine fairytale realities, heaven on earth -- at least for the elite. You can build replicas of manors and wear costumes all you like, but the social order where the lives of millions of servants, workers and tradesmen revolve around the whims of a tiny aristocracy, where everyone had their clearly defined role in the social order, is long gone. A journey into the world of Downton Abbey is a journey into an alternative reality.

With no electricity, no cars (barely there in 1912), no telephone, but gas lighting, railways and the new telegraph, you watch the advent of all of those inventions that make our world today, and experience how they transformed everyday life. You are touched by the spectre of revolution, both the Irish War of Independence in episode one (the driver Tom), and then by the odd socialist (not the servants) after the Russian Revolution.

One key plot device is the delicate treatment of the crucial role that Jewish banking money played a prominent role in the elite's fortunes. Lady Grantham (Cora Crawley) is revealed in passing as an American Jewess, whose money saved the Abbey from bankruptcy, but whose origins are (sort of) a family secret. The outcast, though still privileged, role of Jews in British society is implicitly highlighted by the will of the fourth Earl, the father of the Downton Abbey's Lord Grantham, Robert Crawley. He had put an "entail" on the estate, stipulating that unless Cora produced a male heir (which she didn't), the estate would pass over to the closest male relative in the family, a third cousin.

France's emotional response to the recent tragedy, devoid of reason and ignoring history, just makes matters worse.

France's emotional response to the recent tragedy, devoid of reason and ignoring history, just makes matters worse.  Graham Hancock, Supernatural: Meetings with the Ancient Teachers of Mankind, Anchor, 2005.

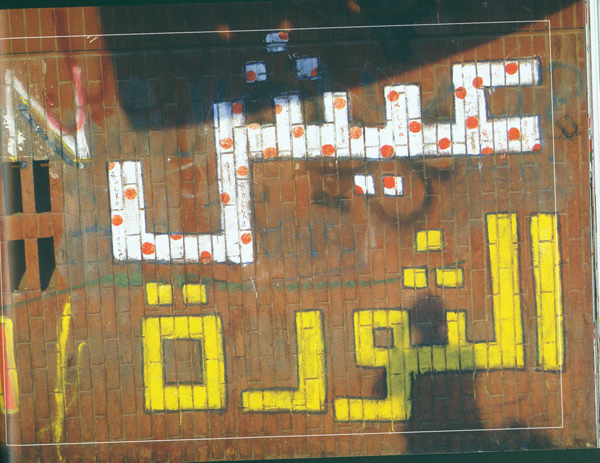

Graham Hancock, Supernatural: Meetings with the Ancient Teachers of Mankind, Anchor, 2005. The Square, a documentary about Egypt’s January 2011 uprising, provides glimpses of most of the players but gives short shrift to the Muslim Brotherhood, the main player that was then targeted by the deep state headed by the military.

The Square, a documentary about Egypt’s January 2011 uprising, provides glimpses of most of the players but gives short shrift to the Muslim Brotherhood, the main player that was then targeted by the deep state headed by the military. The Pinochet-style coup in Egypt in July 2013, 40 years after the Chilean coup, gives pause to reconsider Islamic political strategy. It took Chile 25 year before Pinochet was arrested (ironically, in Britain on a Spanish warrant), and he died eight years later without being convicted at the age of 91. Chilean socialists retook power 27 years after the coup, but their party was no threat to capitalism, a pale ghost of Allende’s revolution. Is this the fate of the Arab Spring?

The Pinochet-style coup in Egypt in July 2013, 40 years after the Chilean coup, gives pause to reconsider Islamic political strategy. It took Chile 25 year before Pinochet was arrested (ironically, in Britain on a Spanish warrant), and he died eight years later without being convicted at the age of 91. Chilean socialists retook power 27 years after the coup, but their party was no threat to capitalism, a pale ghost of Allende’s revolution. Is this the fate of the Arab Spring?