Okay, by bicycle ‘express’. But that was how i saw myself, galloping along the St Lawrence, a watchful eye out for the enemy yonder across the mighty river. The dirt road is now a bicycle lane (sometimes more, sometimes less) that followed--by a stretch of the imagination--the 18th century trail that once bound Canada together.

Forget the mindless 401 hurtling by, for the most part, out of sight and sound. Enjoy the exotic roadside wild flowers shouting “I’m alive and bigger and more beautiful than you!” Some otherwise grueling stretches of highway are transformed into zany public gardens, complete with giant monsters and noxious invaders.

Life in the womb of Upper Canada

A plaque (one of dozens) shames American tourists for their occupation of Fort Matilda in 1813,

near Prescott. Another not far away at Fort Wellington honours Colonel Edward Jessup, who abandoned his half million acre estate in the province of New York to join Loyalists across the St Lawrence in defense of crown and country.

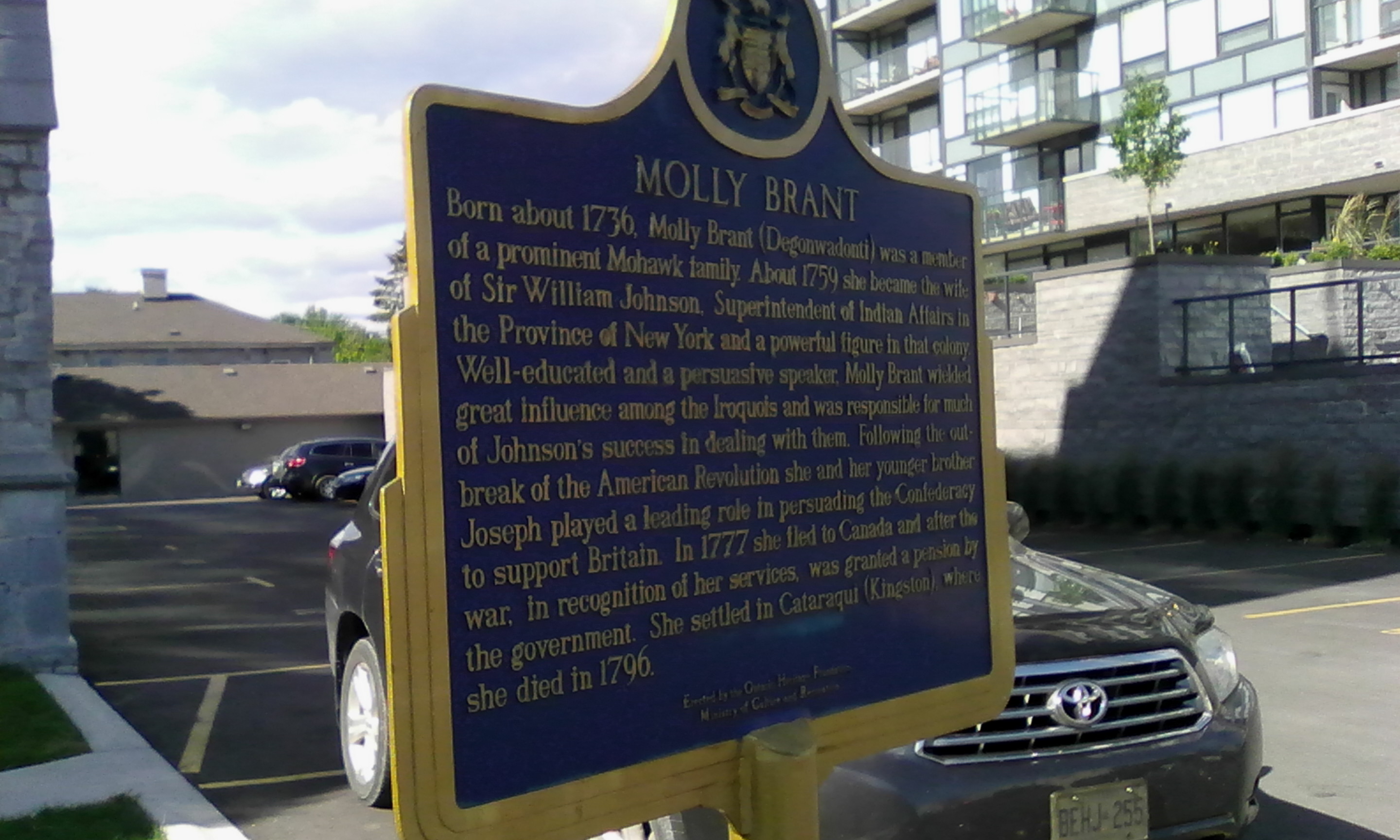

Yet another at St Mary’s Cathedral, Kingston, honours Molly Grant, a native American who married Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs of the province of New York, also a Loyalist. They conspired against the revolutionaries, and after helping the anti-revolutionary ‘confederacy’ in the south, they fled to Canada in 1777.

Suddenly, what it means to be Canadian comes into relief. The Americans were hostile upstarts, even thugs, fighting tooth and nail against everything British, be it good or bad.

Suddenly, what it means to be Canadian comes into relief. The Americans were hostile upstarts, even thugs, fighting tooth and nail against everything British, be it good or bad.

Canadians also had their (similar) gripes, but were not prepared to risk stability for some pipedream. Our heritage is rich, to be proud (okay, and ashamed) of.

Meditative path

Any journey must be an adventure or it’s not worth pursuing. It isn’t easy to get to Kingston for cyclists. There is one Toronto-Montreal train a day that VIA offers with a baggage car – 11:30 am, arriving in Kingston at 2:15 pm and it costs you $28 baggage. Make sure you check with the baggage staff in Toronto before it leaves so they don’t send the bike to Montreal. I made a small placard with KINGSTON on it. No mishap.

The problem is you don’t have much time to get anywhere the first day. I foolishly thought I could start late and bike through Kingston from the train station and still make it to Brockville by sundown. I pulled in (or rather, crawled in) to St Lawrence College, Brockville, at 10pm. Good thing it was June 23, the longest day.

I recommend pokey Gananoque for the first night, just a few hours from Kingston, where I discovered a local eponymous brewery, with first rate beers on tap, in one of the many ‘century buildings’ dotting the entire historic ‘Upper Canada highway’, the now dowdy highway 2, slowly being taken over by cyclists.

I recommend pokey Gananoque for the first night, just a few hours from Kingston, where I discovered a local eponymous brewery, with first rate beers on tap, in one of the many ‘century buildings’ dotting the entire historic ‘Upper Canada highway’, the now dowdy highway 2, slowly being taken over by cyclists.

Mostly bike-friendly

Much of highway 2 sports a modest bike lane, though at times, it is necessary to following religiously the white line separating the cyclist from the whizzing trucks and gravel shoulder. At times, a bit nerve racking, but an experienced cyclist knows that the great feature of highway cycling is that you must be ‘in the moment’. No heavy metal or Brahms blasting your eardrums. The old saw holds: if you are in the moment, God will be there with you.

Brockville has outdone the before- and after-Brockville parts of the trail, with a spectacular path which stretches untouched by inhuman wheels for miles, with the river, islands, and their sometimes comic castles or ghost mansions or just putzy cottages wedged impossibly on Petit Prince type universes.

Even where the paved shoulder peters out, the traffic is light from 6 am to 8 am (make that 5 am, depending on your schedule for the day). You soon learn to cherish these early morning meditation sessions, when time seems to stop—until it kicks in at about 2 pm, by which time you should be within sight of your destination.

Mostly people-friendly

Locals along the route are great. Yes, the Tim Hortons have put the local ma-and-pas out of business, but they are not drive-thru. As long as you spot a local, you can have a nice chat or get reliable directions.

Don’t miss the turn-off to Howe Island 20 km outside of Kingston. I did -- intentionally on the way to Brockville to be sure to get to my destination, and on the way back, as I was looking down most of the time at this point, with a sore neck.

I took the ferry over anyway (my one ferry trip), stopped to rest at a rambling old home. I was parched and figured the white-haired, stooped lady was surely a local, not a johnnie-come-lately retiree, who would know nothing of the history and probably not welcome me.

Jill Quinn brought me out a large glass of her delicious well water. She sat with me on the verandah, and was delighted to tell me of her eight children, three boys still living with her and five girls, all married and now in Kingston. She was born on the island. “I have always cycled, but never bicycled to Kingston,” she said, happy to farm on her beautiful, quiet island, though her sons now work in the city and they grow little.

Doing my taste-testing of the four beers on tap in Gananoque, I was accosted by a brainy young local, and we were soon in a discussion of post-structuralism and Derrida. Alex is doing his PhD and teaches in Nunavik. He was home visiting his parents. The romance of a solo bike odyssey opens many doors.

The Goal

The journey is the goal. But also a pilgrimage. At the farthest reach of the 1000 Islands is Ground Zero of the St Lawrence Seaway, the Long Sault Dam, on the western outskirts of Cornwall.

Cornwall’s glory days were two centuries ago, established in 1784 by United Empire Loyalist troops. It reached its zenith in the era of the railways and the canal system linking Ottawa and the St Lawrence. It is a modest 50,000 population today, better known for its bridge to the US, and the St Lawrence Seaway.

This project, which Canada began in 1951 and financed most of, is the beginning and end of North America’s amazing inland waterway. It finally got Eisenhower on board, and opened in 1959. The capstone dam is not impressive, only 81 feet high.

What is impressive is what it drowned: the spectacular Long Sault Rapids, and the nine ghostly Lost Villages. The damming in 1952 was a great loss to  kayakers, but a boon to General Motors, Reynolds Metals and the Aluminum Company of America.* You cycle over one of the nine Lost Villages, Mille Rouches, on the Long Sault Parkway, a string of islands created by the damming of the Long Sault Rapids. That section and the final leg to Cornwall through the woods are truly a cyclist’s heaven.

kayakers, but a boon to General Motors, Reynolds Metals and the Aluminum Company of America.* You cycle over one of the nine Lost Villages, Mille Rouches, on the Long Sault Parkway, a string of islands created by the damming of the Long Sault Rapids. That section and the final leg to Cornwall through the woods are truly a cyclist’s heaven.

I was staying just short of Cornwall, near Morrisburg, a key location of 1812--13 war, which the locals are proud of, and which has many commemorative plaques. Trying to educate the American visitors, who are oblivious (“1812? Never heard of it.” or at best, “We won the war of 1812 against Britain.” The Brits dismiss it as the "American war of 1812").

High tech defense, high tech transport

The victory in what Canadians proudly call the War of 1812 prompted the Canadians and British to upgrade defenses, building the state-of-the-art Fort George in Kingston (1838). It, mercifully, never fired a  shot, a bit like Reagan’s Star Wars, though the cost was not in vain. The fort’s impregnability surely helped deter the insatiable US hunger for Canadian lands, making the budding empire-builders look elsewhere.

shot, a bit like Reagan’s Star Wars, though the cost was not in vain. The fort’s impregnability surely helped deter the insatiable US hunger for Canadian lands, making the budding empire-builders look elsewhere.

*They opened factories and proceed to severely polluted the river. Lawsuits have resulted in Superfund clean-up sites and some redress to local natives and poor Nature.