We left Saturday morning for a 4-day hike. Because of the growing problem of bandits in the mountains, Sasha decided to start from the mountains nearest to Tashkent which start from a Tajik village (all villages near or in the mountains are populated by either Tajik or Kazakh) called Nevichu, avoiding check points by taking back roads. Sasha’s wife, Oksana, (whom I met on the plane from New York to Tashkent when she conned me into taking one of her 50-lb. bags to avoid extra baggage charges) saw Sasha, their son, Dima, and myself off, agreeing to meet us 5 days later in Gazalkent.

We left Saturday morning for a 4-day hike. Because of the growing problem of bandits in the mountains, Sasha decided to start from the mountains nearest to Tashkent which start from a Tajik village (all villages near or in the mountains are populated by either Tajik or Kazakh) called Nevichu, avoiding check points by taking back roads. Sasha’s wife, Oksana, (whom I met on the plane from New York to Tashkent when she conned me into taking one of her 50-lb. bags to avoid extra baggage charges) saw Sasha, their son, Dima, and myself off, agreeing to meet us 5 days later in Gazalkent.

The plan was to skirt the Chatkal nature sanctuary, following the Chatkal ridge, and spend the next 4 days at 3000 meters, including two peaks at 3300. Rather ambitious, as it turned out.

We set out, gung-ho, climbing the treeless ridge, raising clouds of yellow dust, and leaving the few day-tourists behind. Soon we were skirting the various peaks as we moved gradually up the massive ridge. We came upon a shepherd, some evidence of former geological surveying from Soviet times (all such luxuries stopped abruptly with independence), and were attacked by hordes of butterflies. Some canned salmon provided a late lunch and we proceeded for another few hours, finally calling a halt on a beautiful mountain meadow. Water was urgently needed, but Sasha insisted that all the greenery indicated that somewhere below there should be a spring. He and Dima set out, leaving me as guard dog, which suited me fine as I was exhausted. Ah, indulging in a fag and a sip of vodka with 360 degree of heaven around! I promptly snoozed off. That few minutes was to be much more successful than my desperate attempts that night to sleep. I had forgotten the travails of tent-sleeping, and that night I was downhill of Dima and (snoring) Sasha, with my head lower than my feet. I actually had an attack of claustrophobia after trying to meditate myself to sleep for several hours and ended up crouched in a ball at their feet the rest of the night, finally nodding off in the wee hours of the morning.

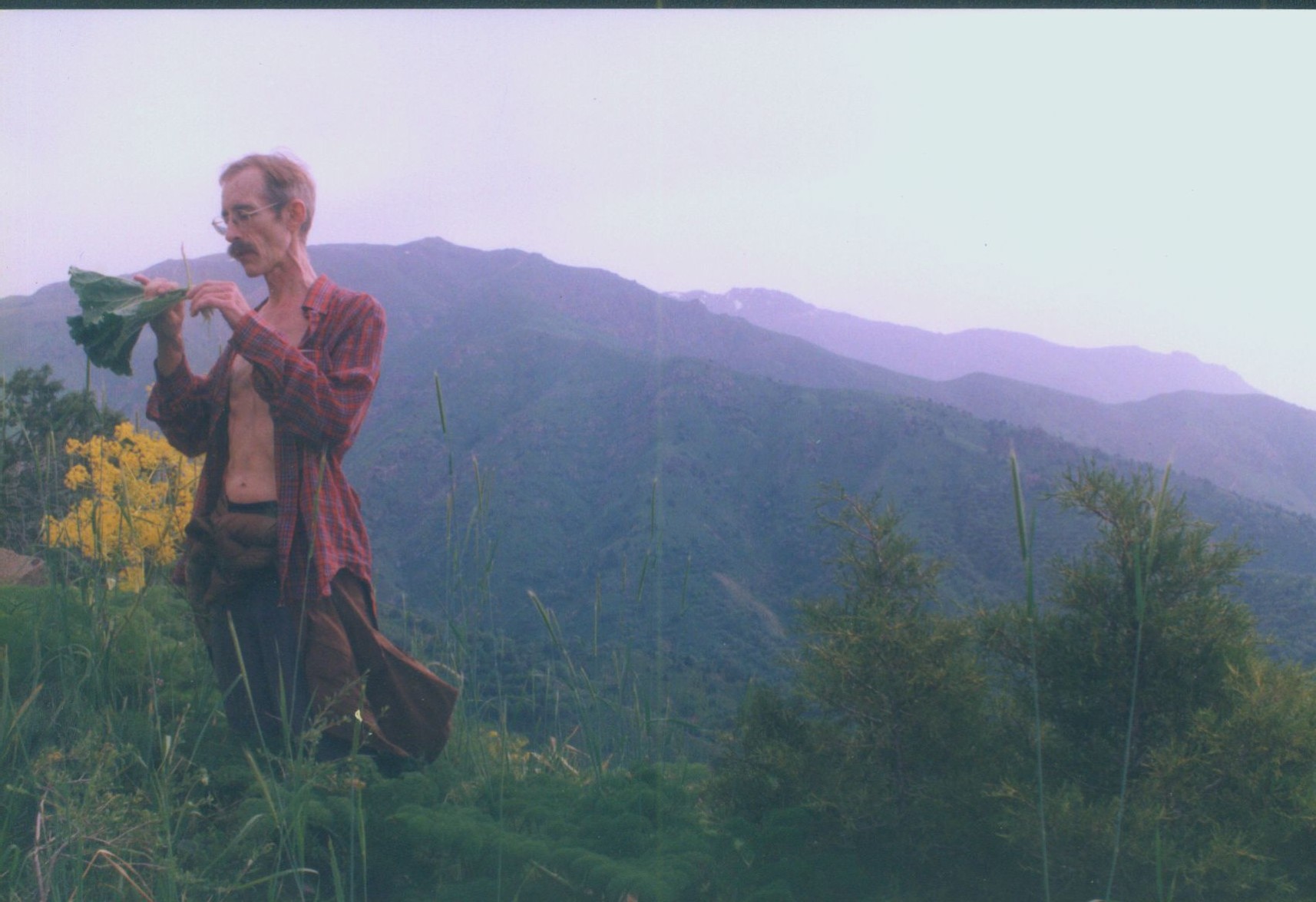

The second day (by the way, glorious sunshine the entire time) was more of the same, though nothing is ever quite the same in the mountains. Each second, each breath (especially in the spring), each step is an event. We happened on cold springs, lots of wild rhubarb which we sucked and chewed at, eagles soaring curiously, until, rounding one bend and descending rather more than we expected, the trail petered out. We scouted around and found a hunter’s lean-to. We eventually found what we assumed to be the path marked on Sasha’s surveyor’s map and followed it around and up a steep ridge, but at the top, it finally gave out for good. It turned out we were on the wrong side of the Great Takosy mountain peak, and we realized we would now have to climb right up the peak and down the other side to find the real path, as the incline on either side was too severe.

Without a path at these heights, heaven becomes hell! It was already 4:30, and we were quite exhausted, so we pitched camp on the narrow ridge top, scraped up some twigs and rationed our meager water supply, allowing ourselves only tea, corned beef and bread, leavened by a shot of vodka for Sasha and me. I spread out my sleeping bag on a rocky lounge chair and started Durrel’s Balthazar. However, the prospect of climbing this imposing peak (sans path) and what was shaping up as a grueling and rather dangerous trudge at these unforgiving heights weighed me down and with nothing better to do, I joined the heavy sleepers. Another night of tossing and turning, listening to the wind rise and fall, beating off Dima’s elbow or head (I apparently make a good pillow).

After a few winks, the sun came up and soon made our tent a high-altitude oven. Even bleary I was glad to get out. We had more tea and corned beef (ugh) and started our uncharted climb. Real mountaineering - hugging outcroppings, grabbing branches, puffing away. Finally we were on top. Wow! Even the snow-capped Pamirs in Tajikistan were visible. And we found the path on the other side, a narrow thread a 100 meters down, and gratefully joined it. How much difference a 6 inch sliver of path makes on an otherwise almost sheer drop. Rounding a curve, there were snow banks. I suggested we fill our bottles with the albeit slightly dirty snow just in case (springs are few and far between at these heights). Sasha wasn’t interested, so we continued on, descending to another link in the ridge.

At a rest stop suddenly two brown, short-haired mountain goats appeared, clearly startled by this new breed of mountain goat, and hopped gracefully down the slopes leaving their two-footed cousins to marvel at their pas de deux. As they rushed away, Sasha announced that due to lack of water we would change our route, descending into the nature sanctuary to certain water below, and following the river back to Nevichu, though it is strictly forbidden to hike in the sanctuary. We had lost half a day after losing the path and the original route now seemed too ambitious, involving reaching another peak of over 3000 meters that day. Dima had been dragging his feet a bit, and Sasha, at 80 kgs needed lots of water. I demurred though I dreaded the descent through bushes and water rushes without a path and the hike along a river for miles without a path. That’s not fun, jumping from rock to rock, constantly risking twisting your ankle (which I have done 3 times), maneuvering down steep canyons where waterfalls can make your way impassable. And all in a forbidden sanctuary (the politically correct Greenpeacer in me protesting).

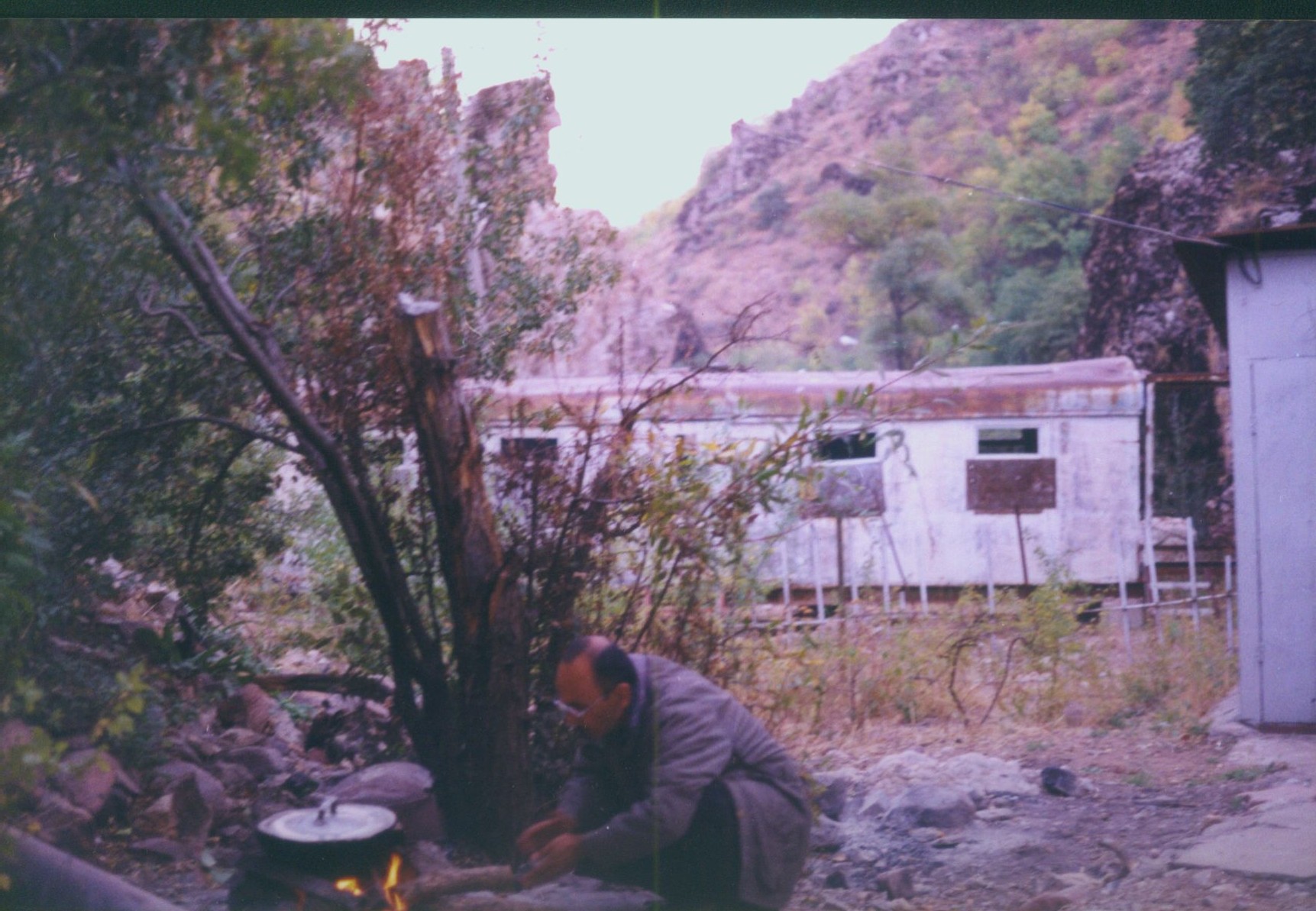

So this, the third day, turned out to be a bit of a nightmare. Sasha drove us hard from dawn till dusk. Having started at 7:00 am by scaling Great Takosy, we now were sliding and stumbling down to the river, and then crossing it back and forth a hundred times, crashing through underbrush, slipping around waterfalls (my pack descending a 5-meter waterfall without me, soaking the macaroni and candies). We finally reached signs of human encampment (the dreaded inspectors), and gratefully followed their horse trail, which no less frequently crisscrossed the river, but saved us the need to debate where we could navigate and where we couldn’t. A horse trail differs from a human trail in that horses don’t need to jump from rock to rock, but willingly get their hooves wet. So we resigned ourselves to squishy feet from mid-afternoon on. By 6:30 we finally collapsed at what turned out to be a beautiful campsite. In fact the whole day was full of spectacular scenery, canyons, waterfalls, lush mountain greenery, crystal clear mountain water everywhere. Paraphrasing the old adage: water, water, everywhere, and all of it potable.

I pulled out the chocolate, poured Sasha and myself the last of the vodka, and praised the Lord that we were all still in one piece, physically and as a group. In fact, the sleepless nights, and Sasha and Dima’s habit of throwing away cans and even abandoning plastic bottles (damn those disposable 1.5 liter bottles - may Coke&Co rot in hell) were getting on my nerves. (To be fair I should really do a Roshamon and get their side of the story). However, we were in this together, and despite the snoring and trash, Sasha clearly loved nature in his own way. And I was sooo tired at this point, that after a few chapters of Balthazar I was able to get to sleep with only a few hours of tossing and turning, and lasted most of the night. Hurrah!

I pulled out the chocolate, poured Sasha and myself the last of the vodka, and praised the Lord that we were all still in one piece, physically and as a group. In fact, the sleepless nights, and Sasha and Dima’s habit of throwing away cans and even abandoning plastic bottles (damn those disposable 1.5 liter bottles - may Coke&Co rot in hell) were getting on my nerves. (To be fair I should really do a Roshamon and get their side of the story). However, we were in this together, and despite the snoring and trash, Sasha clearly loved nature in his own way. And I was sooo tired at this point, that after a few chapters of Balthazar I was able to get to sleep with only a few hours of tossing and turning, and lasted most of the night. Hurrah!

We continued on the horse trail, both loving the inspectors for having maintained it, and dreading meeting them and finding out the consequences of our violating the sanctuary. The trail soon climbed the valley walls and we had dozens of spectacular views of the canyon below and the ridges above. We saw wild boars, traces on the trail of bears. Dima had an altercation with a tarantula which made feints at him as he walked past; no doubt it was guarding its nest. There were frequent springs and cool glades to rest under between the bouts hiking up and down in the intense desert sun. Sasha sensibly had us wear our T-shirts under our caps to keep the sun off our heads, ears and necks. That was essential to prevent sun-stroke, as I now realize.

All the time, we saw lots of horse droppings, recent campfires, finally a destroyed lean-to. Rounding one bend, there they were - the dreaded mountain police. In fact, they were two Tajik locals from Nevichu, who very politely showed us their documents and shook hands. The leader, Zhora, as he introduced himself with a Russian diminutive, put his hand on his heart, in the delightful Muslim tradition to show respect, and proceeded to explain that this was a sanctuary, etc., etc. He was short but athletic, missing a few teeth with a few others capped in gold, but with the traditional Tajik flashing eyes and well-shaped face. I thought Sasha was quite cool, even a bit rude, explaining that we got lost and didn’t realize etc., etc.

Zhora: Can you show me a document? [everyone must be ready to do this in this part of the world]

Sasha: I don’t have any documents with me. I’m nobody. I don’t work now. I hike often in these parts and I know half the village of Nevichu, so don’t try to push me around.

Zhora (surprisingly polite, considering what militia are like here): By law we should search and confiscate all your belongings, take you back to the station and issue a fine which you will have to pay in Parkent [the town nearest the sanctuary].

As they stared each other down, Inspector #2 (half-heartedly to me): Please show me your document.

I decided I should play the cop-good to Sasha’s bad-cop (or rather defendant) and willingly pulled out my passport. Inspector #2 looked at it, first this way and then that way, not sure what to make of it. Zhora pulled out his forms for the fine and thrust a notebook into Sasha’s hands, instructing him to put in writing how we happened to be there.

Meanwhile, I struck up a conversation with Inspector #2.

Eric: What are you doing here today?

#2: We have been instructed to destroy the lean-tos. You know about the Wahibisti bandits in the mountains. It’s getting more dangerous. That’s why we must be strict about people being here without authorization.

Eric: What is the sanctuary for?

#2: It was founded in 1947 to preserve as much of the natural habit as it was before. Recently there was a conference with Germans here to see it. There is no hunting or tourism.

It crossed my mind that I rather approved of keeping garbage-throwing tourists and hunters out. Sasha later pooh-poohed these high-flown words of #2: You want a wild boar? Give him a hundred bucks and he’ll be delighted to hunt one down and give you. People here quietly go about hunting in the sanctuary because they don’t have enough to eat.

The upshot was that Zhora wrote out my name and address, declined to seize or even search our things (“That would just be a headache for us both”) and told Sasha he should pay the fine to the office, “maybe in Tashkent - I’ll explain to my boss.” Surprisingly, there was no hint that they wanted a bribe, which I would have been glad to pay, to put paid to the matter. In fact, Zhora said, “I need to show my boss I’m catching violators.” Such a nice change from the despicable cops in Tashkent or on the road, stopping you for trumped up violations in order to extract bribes. As they went on their way, Zhora shook my hand again, and suggested I come again and go horseback riding.

It was actually a relief to be caught and to be penitent. The remaining hike through the sanctuary could now proceed without guilt, though the heat at 1000 meters was rather oppressive and everything hurt - back, legs, shoulders, head, hands (burnt to a crisp), feet (blisters and the treads completely in shreds). Trudge, trudge, the last hours are always the longest, knowing that you are near the end. We walked up the dirt road and stopped for yet another corned beef and bread lunch (ugh, ugh, UGH) under a majestic, gnarled tree. Sasha refused the corned beef, but commented: “Have some wild cherries.” I looked up and hundreds of delicate deep red berries glistened in the blazing sun. Reminiscent of chokecherries, they may a fitting sweat/sweet-sour desert for our humdrum repast.

We climbed our last hill, passing under the rickety tin arch of the sanctuary entrance (are these what the pearly gates will look like?) and looked out over the plain below. However, in the foreground loomed a massive black 2001 monolith, set on its side, with an appropriately-sized monolith table, huge and menacing.

“What is this monster?” I asked Sasha. “It was built in Soviet days as part of the Star Wars top secret defense program. When the Soviet Union collapsed, it was abandoned.” ‘Hmmm,’ I thought. ‘Does that mean that the velvet Soviet words of peace really hid a steel fist?’ This monster has to be seen to be believed. After the exquisite sights of the sanctuary, this was like a something out of a sci-fi hell.

We limped down towards Nevichu, passed some friendly drunken Tajiks who tried to ply us with tea, past some kottezhy, most likely rest spots for the Star Wars workers of yesteryear, through a rusty gate and back alleys to the river, which was no longer potable, but clean enough for a dip to bring us back to life for the still long trip back to home, sweet home in Tashkent. We took a bus to a country crossroads, and began waiting for another to take us another few miles to the regional center, Parkent.

At the country bus stop, we indulged in several liters of fresh sour milk (not a contradiction in terms) for about $.25. As I spooned down my treat, a leather-faced crazed babushka railed at me in Tajik. The milklady translated: She wants you to sit down to enjoy your meal. Babushkas are the same the world over, sane or otherwise. A moment later, she grabbed my ski pole cum mountain staff and began wielding it over her head at another babushka. I decided: enough local colour; let’s get home! A taxi 5 miles to Parkent of sanctuary fame - cost us $.50, and took us over a majestic rolling plain of beautifully manicured crops, wheat already ripe, with the glorious Tien Shan mountains as a backdrop.

Ah, Parkent! Home of Uzbekistan’s contribution to 21st c energy - a huge (‘Soviet computers are the biggest computers in the world’) experimental solar panel built decades ago which is still experimenting (Get on with it!). The town itself is a pokey, dirt poor backwater. I’m sure no one there has any idea about solar power. We caught our bus to Tashkent - an ancient, creaking, farting Lvov hunchback, which had to be hand-cranked to start, and which kept sputtering and conking out at each stop.

I’m now planning my next bike trip. Yes, to funky ol’ Nevichu. Maybe I’ll see the sanctuary by horseback.