All the meticulous plotting to avoid Ukraine’s Orange Revolution

resulted in -- Russia’s very own coloured one. But Russia is not

Ukraine, discovers Eric Walberg

All the meticulous plotting to avoid Ukraine’s Orange Revolution

resulted in -- Russia’s very own coloured one. But Russia is not

Ukraine, discovers Eric Walberg

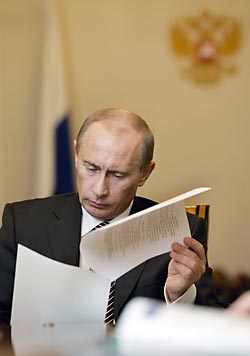

Russia’s electoral scene has been transformed in the past two months,

without a doubt inspired by the political winds from the Middle East and

the earlier colour revolutions in Russia’s “near abroad”. Prime

Minister Vladimir Putin’s casual return to the presidential scene was

greeted as an effrontery by an electorate who want to move on from

Russia’s political strongman tradition, and to inject the electoral

process with ballot-box accountability.

Putin’s legendary role in rescuing Russia from the economic abyss in the

1990s, staring down the oligarchs, reasserting state control over

Russian resource wealth, and repositioning Russia as an independent

player in Eurasia (not to mention in America’s backyard) -- these signal

accomplishments assure him a place in history books. He and Dmitri

Medvedev are considered the most popular leaders in the past century

according to a recent VTsIOM opinion poll (Leonid Brezhnev comes next,

followed by Joseph Stalin and Vladimir Lenin, with Mikhail Gorbachev and

Boris Yelstin the least popular). He will very likely pass the 50 per

cent mark in presidential elections 4 March, despite all the protests

during the past two months calling for “Russia without Putin”. So why is

he back in the ring?

It appears he was caught by surprise when the anti-Putin campaign

exploded in November, fuelled by his decision to run again and the

exposure of not a little fraud in the parliamentary elections in

December. For the first time since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the

opposition was able to unite  and stage impressive rallies, one after

another. Despite the chilling Russian winter, they keep coming -- this

week saw four gathering around Moscow, totalling 130,000.

and stage impressive rallies, one after

another. Despite the chilling Russian winter, they keep coming -- this

week saw four gathering around Moscow, totalling 130,000.

The opposition poster children even include Putin’s minister of finance

Alexei Kudrin. Presidential hopefuls are Communist leader Gennadi

Zyuganov (backed for the first time by the independent left forces),

nationalist Vladimir Zhirinovsky, A Just Russia’s Sergey Mironov and the

oligarch playboy Mikhail Prokhorov -- none of whom stand a chance of

defeating Putin. This time there are 25 televised debates which began 6

February among the contenders, who are sparring with each other and

“Putin’s representative”.

Is this quixotic march back to the Kremlin heights a case of egomania?

Or is it a noble attempt to both cast in stone Russia as the Eurasian

counterweight to an increasingly aggressive US/NATO, and shaking up the

domestic political scene to make sure it will not slump into apathy when

he himself passes the torch? And if things go wrong, is this Russia’s

very own White Revolution, long feared by the Russian elite, and long

coveted by Western intriguers?

Russian politics has always confounded Western observers, and continues

to do so. Putin is famously imperious and gets away with it. He taunted

the opposition by saying he thought the original demonstrations were

part of an anti-AIDS campaign, that the white ribbons were condoms. But

he nonetheless sanctioned the largest political opposition rallies in

the past 20 years.

US democracy-promotion NGOs such as the National Endowment for Democracy

-- a key player in Ukraine’s 2004 Orange Revolution -- are active in

Russia’s opposition, but Putin is clearly gambling that Russians can see

past US efforts to manipulate them. Besides, the winners in the Duma

elections were the Communists and nationalists, with pro-Western

liberals placing a distant fourth -- hardly the results NEDers would

have wanted.

He is also famously willing to tell US politicians they wear no clothes

-- the latest, last week in Siberia: “Sometimes I get the impression the

US doesn’t need allies, it needs vassals.” Russian foreign policy is

now firmly anti-NATO, both with respect to the West’s misguided missile

system and its eagerness to turn Syria into a killing fields. Rumours

that a Russian Iran-for-Syria deal with the West have proved empty.

There are even hints that Iran may still get its defensive S-300

missiles from Russia in exchange for Russian access to the downed US

drone. Iran claims to have four already and recently announced they have

developed their own domestic version.

Pro-Putin rallies are almost as large as the opposition’s, with an

official count of 140,000 attendees at the festive gathering Saturday.

The Putinistas even bill theirs as the Anti-Orange rally. “We say no to

the destruction of Russia. We say no to Orange arrogance. We say no to

the American government…let’s take out the Orange trash,” political

analyst Sergei Kurginyan exhorted at Moscow’s Poklonnaya Gora war

memorial park. Putin thanked organisers, commenting modestly, “I share

their views.”

The real reason for Putin’s return is due to the failure during his

first two terms of his “sovereign democracy” to limit corruption in

post-Soviet Russia. Instead, of producing a modernising authoritarianism

along the lines of post-war South Korea, Putin’s rule deepened

corruption -- the bane of late Soviet and early post-Soviet society.

Instead of trading political freedom for effective governance, he

clipped Russians’ civil and political rights without delivering on this

vital promise. Neither did he end collusion between the state and the

oligarchs. That was the handle that badboy Alexei Navalni used to

catalyse the opposition around his slogan that United Russia is the

“party of swindlers and thieves”.

This was the scene in the 2000s in Ukraine, where it was possible for

the NEDers to undermine the much weaker Ukrainian state and install the

Western candidate Viktor Yushchenko in 2004. However, instead of

addressing the problems that led to the Orange Revolution, Putin

focussed on foreign threats to Russian political stability rather than

paying attention to domestic factors, creating patriotic youth

organisations such as Nashi (Ours) and the 4 November Day of Unity

holiday – the latter quickly hijacked by Russia’s nationalists.

But Russian fears of Western interference are hardly naïve. Russia was

sucked into the horrendous WWI by the British empire, suffered

devastating invasions in 1919 and 1941, and another half century of the

West’s Cold War against it. Further dismemberment of the Russian

Federation is indeed a Western goal, which would benefit no one but a

tiny comprador elite, Western multinationals and the Pentagon.

Putin’s statist sovereign democracy – with transparent elections – might

not be such a bad alternative to what passes for democracy in much of

the West. His new Eurasian Union could help spread a more responsible

political governance across the continent. It may not be what the NED

has in mind, but it would be welcomed by all the “stan” citizens, not to

mention China’s beleaguered Uighurs. This “EU” is striving not towards

disintegration and weakness, but towards integration and mutual

security, without any need for US/NATO bases and slick NED propaganda.

The union will surely eventually include the mother of colour

revolutions, Ukraine, where citizens still yearn for open borders with

Russia and closer economic integration. The days of dreaming about the

other EU’s Elysian Fields are over. The hard, cold reality today has

bleached the colour revolutions, making white the appropriate colour for

Russia’s version of political change.

Of course, the big problem -- corruption -- is what will make or break

Putin’s third term as president. At the Russia 2012 Investment Forum in

Moscow last week, Putin outlined plans to move Russia up to 20th spot

from its current 120th in the World Bank index of investment

attractiveness, by reducing bureaucracy and the associated bribery.

“These measures are not enough. I believe that society must actively

participate in the establishment of an anti-corruption agenda,” he

vowed. Reforming the legal system and expanding the reach of democracy

will be key to fighting corruption, not just via presidential decrees,

but through empowering elected officials and voters. He confirmed this

in his fourth major pre-election address this week by promising to

provide better government services by decentralizing power from the

federal level to municipalities and relying on the Internet.

So far things look good. For the first time since 1995 there will be a

hotly contested transparently monitored presidential election, with the

distinct possibility of a runoff (unless the new US Ambassador Michael

McFaul keeps inviting NED darlings to Spaso House). The sort-of

presidential debates, large-scale opposition rallies and the new

independent League of Voters intending to ensure clean elections are a

fine precedent, making sure that this time and in the future there will

be an opportunity for genuine debate about Russia’s future.

Despite all attempts to forestall Russia’s colour revolution, it has

begun -- Russian-style -- with no state collapse, but with a new

articulate electorate, wise to both Kremlin politologists and Western

NGOlogists. Its final destination is impossible for anyone to predict at

this point.