[Updated 2014] Awards have become less and less controversial, especially since the US imperial ascendancy in 1991.

With the rise of Hitler, the Peace Prize committee finally mustered up the courage to take on Nazism, and awarded the 1935 prize to Carl von Ossietzky, a German journalist and pacifist who had spent several years in Papenburg-Esterwegen, a Nazi concentration camp, convicted of high treason and espionage in 1931 after publishing details of Germany's violation of the Treaty of Versailles by rebuilding an air force and training pilots in the Soviet Union. (Ironically, the verdict was upheld by the Federal Court of Justice in 1992.) At the time it was a highly controversial decision (though not with anti-fascists), with two jury members resigning, fearing a political fallout with the Nazis.

Goring tried to pressure Ossietzky into refusing the award, and he was not allowed to collect it or send  an acceptance speech, dying in prison in 1938 as a result of his brutal treatment. The precedent was set, however, and future human rights campaigners such as South African Albert Luthuli (1960), Linus Pauling (1962), Martin Luther King Jr (1964), Andrei Sakharov (1975), Argentinian Adolfo Perez Esquivel (1980), the Dalai Lama (1989), Aung San Suu Kyi (1991), East Timorese Bishop Carlos Belo and Jose Ramos-Horta (1996), Liu Xiaobo (2010), and Malala Yousafzai (2014) have similarly suffered from their activities.

an acceptance speech, dying in prison in 1938 as a result of his brutal treatment. The precedent was set, however, and future human rights campaigners such as South African Albert Luthuli (1960), Linus Pauling (1962), Martin Luther King Jr (1964), Andrei Sakharov (1975), Argentinian Adolfo Perez Esquivel (1980), the Dalai Lama (1989), Aung San Suu Kyi (1991), East Timorese Bishop Carlos Belo and Jose Ramos-Horta (1996), Liu Xiaobo (2010), and Malala Yousafzai (2014) have similarly suffered from their activities.

After WWII, the selection committee was reformed to include members other than Norwegian politicians, and in 1977, serving MPs were actually excluded. As the UN grew in stature, it and other international organizations continued to be the focus of awards (Dag Hammarskjold, the UN itself, UN peacekeeping forces, the UNHCR, the ILO, the Red Cross, UNICEF, the IAEA, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). However, women, human rights activists and campaigners from the 3rd world were increasingly awarded the prize.

One early postwar recipient now forgotten is Ralph Bunche (1950), the first nonwhite to be awarded, for his work in the UN negotiating the first peacekeeping force between Israel and the Arab nations. Bunche was an African-American academic and UN diplomat, and was forced to take over the negotiations from the Swedish Count Folke Bernadotte of Wisborg who was assassinated by Israeli terrorists. After more than a year of painstaking negotiations, Bunche managed to secure separate armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt, Lebanon, Transjordan, and Syria, which left Israel with all the territory it had conquered, hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees, and no state of Palestine. Only by Middle East standards could it be considered a success. As you might expect, his speech was so riddled with diplomatic niceties, he avoids mentioning why he was so unexpectedly thrust into the limelight, or that the truce was less than fair. Still, at a time when the civil rights movement was gathering steam in the US, this award no doubt carried an added message.

The glaring failure of the Nobel Peace Prize which became clear by its mid-century was its timidity and even perversity with respect to the great issue of the postwar world -- détente. There is scarcely a word in any of the acceptance speeches dealing with the most central issue to the struggle for peace in the 20th c.

The schism of the 1930s between fascism and communism, and the Nobel committee’s fundamental anti-communism was of course behind this glaring omission. In 1938, it even shortlisted Hitler along with Gandhi for the prize. Though outrageous today, at the time many in the West regarded the fuhrer as a bulwark against Bolshevism. Such an outstanding figure as Gertrude Stein even said: "Hitler ought to have the peace prize, because he is removing all the elements of contest and of struggle from Germany… By suppressing Jews he was ending struggle in Germany.” (New York Times, 1934). But then he was Time magazine’s Man of the Year in 1938 and was honored with an appreciative profile.

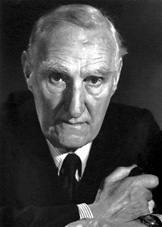

After scouring speech after speech, I found only 4 laureates who had a good word for detente. The laureate who mostly nobly resisted this sad trend was the rather unlikely Lord Boyd Orr, head of the Food and Agriculture Organization from 1945-8, who won in 1949. While his driving passion was increasing food production and improving diets, he was not afraid to buck the growing Cold War  hysteria which had been unleashed in 1946 by another British statesman and Nobel laureate (for literature 1953), Sir Winston Churchill, with his notorious "Iron Curtain” speech just a few months previously. Orr too condemned Russia’s gulags but insisted (remember, this is at the nadir of the Stalinist police state) that we should be patient, that the excesses will inevitably end, and that, most important, that confrontation would not lead to world peace. Brave words. I’ll let you decide which British statesman better served the cause of peace.

hysteria which had been unleashed in 1946 by another British statesman and Nobel laureate (for literature 1953), Sir Winston Churchill, with his notorious "Iron Curtain” speech just a few months previously. Orr too condemned Russia’s gulags but insisted (remember, this is at the nadir of the Stalinist police state) that we should be patient, that the excesses will inevitably end, and that, most important, that confrontation would not lead to world peace. Brave words. I’ll let you decide which British statesman better served the cause of peace.

Some excerpts from Orr’s acceptance speech:

On hopes for a disarmament treaty This is a vain hope. When gunpowder was introduced, it was considered such a barbaric weapon that it was banned by the church except, of course, against heretics. That did not prevent the use of artillery… The only restraint is the fear of reprisals. In the last war the USA, which had no fear of reprisals, did use [the atom bomb]. In another war those in power, with the memory of the fate of Hitler and his associates in Berlin and in the Nuremberg trials, will not hesitate in a last desperate effort to throw in every weapon in their power.

The road to peace lies only through the cooperation of governments on a world scale to apply science to develop the resources of the earth for the benefit of all. Though doing good work, [the UN and its specialized agencies] are not functioning to their full capacity because governments are devoting too much energy to preparing for a war which will most probably never come and to political issues which will never be settled by controversy.

On East-West relations The present tension cannot be relieved by propaganda of fear and hate. It might be relieved by a new approach, in which each power, beginning with the one which feels surest of its own position, would give full and even flattering credit to every worthwhile achievement in the other, ignoring, as far as they can be ignored, issues which cause disagreement.

Thus, for example, let our communist friends admit that the worst evils of a ruthless capitalism, which Karl Marx saw in England and rightly hated, have disappeared. The capitalist system is being transformed from within and is proving so successful in creating wealth and raising the standard of living, while at the same time enlarging the individual freedom of the workers, that there is little hope of people exchanging their way of life under which they are doing so well for an alien ideology. Foolish attempts to undermine it by a propaganda of half-truths merely rallies people to its support and alienates many friends of Russia. Let our friends in Russia give the democratic countries credit for the great advance they have made and realize that this course of peaceful evolution will be followed in all countries where the people are educated and have freedom to read what they like and to discuss and criticize governments.

On the other hand, let the Western countries give full credit to what the USSR has done against appalling difficulties, including the hostility of capitalist countries, in its great expansion of technical education, in its public health work in some aspects of which it seems to be in advance of almost any country, and in its astonishing agricultural and industrial development. Young people who have been indoctrinated with the communist ideal and know little or nothing of the achievements of other countries believe that they are building a new and better world, and, compared with the conditions of the old medieval rule of the Czars, they have some ground for their enthusiasm. Attack on the system merely strengthens their faith, and the fear that their work may be destroyed by attack by the capitalist countries makes them willing to make any sacrifice in the preparation of a war of defence.

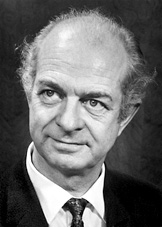

Linus Pauling, the only winner of two Nobel prizes (1954 Chemistry and 1962 Peace), was the next recipient who took détente and a greater understanding of the Soviet Union seriously. He had been a  member of Einstein's Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, which was active from 1946 to 1950. No doubt because of this and despite his prestige as a winner of the chemistry award in 1953, he was refused a passport by the US State Department in 1954. In 1958, he presented to the UN a petition signed by 9,235 scientists from around the world protesting further nuclear testing. In that same year he published No More War!, a book which presents the rationale for abandoning not only further use and testing of nuclear weapons but also war itself, and which proposes the establishment of a World Peace Research Organization within the structure of the UN to "attack the problem of preserving the peace".

member of Einstein's Emergency Committee of Atomic Scientists, which was active from 1946 to 1950. No doubt because of this and despite his prestige as a winner of the chemistry award in 1953, he was refused a passport by the US State Department in 1954. In 1958, he presented to the UN a petition signed by 9,235 scientists from around the world protesting further nuclear testing. In that same year he published No More War!, a book which presents the rationale for abandoning not only further use and testing of nuclear weapons but also war itself, and which proposes the establishment of a World Peace Research Organization within the structure of the UN to "attack the problem of preserving the peace".

His efforts led to president John F Kennedy's signing of the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, outlawing all but underground nuclear testing, which went into effect on 10 October 1963, the same day the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced that the Peace Prize reserved in the year 1962 was to be awarded to him. In his acceptance speech he said: "The world has now begun its metamorphosis from its primitive period of history, when disputes between nations were settled by war, to its period of maturity, in which war will be abolished and world law will take its place.” He saw the test ban treaty as "the first of a series of treaties that will lead to the new world from which war has been abolished forever. The first of a series of treaties that will lead to the new world from which war has been abolished forever.” (Contrast this with Orr’s distrust of disarmament treaties.)

This was surely the high point of postwar détente -- the Cuban missile crisis was safely behind us, and Kennedy, chastened by both it and the Bay of Pigs scandal, looked ready to talk seriously with the Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev about a new world order. If we are to believe the Oliver Stone school of thought, Kennedy was assassinated precisely because he was about to make a sea change in US foreign policy, embracing détente and making an about-face on Vietnam. But that, alas, is all in the land of Camelot.

There were only two other laureates with a real interest in promoting détente – Willy Brandt (1971)  and Le Duc Tho (1973). The latter refused to accept the award (the only time this has happened to date), while the former was hounded from office precisely because

and Le Duc Tho (1973). The latter refused to accept the award (the only time this has happened to date), while the former was hounded from office precisely because  of his openness to détente. Further recipients who had a stake in détente, such as Henry Kissinger (1973), Andrei Sakharov (1975), and Lech Walesa (1983), were eager only to drive their 'stakes' through the heart of the Soviet system itself.

of his openness to détente. Further recipients who had a stake in détente, such as Henry Kissinger (1973), Andrei Sakharov (1975), and Lech Walesa (1983), were eager only to drive their 'stakes' through the heart of the Soviet system itself.

Sakharov, to his everlasting shame, was an enthusiastic supporter of the US war in Vietnam at the time he was awarded the prize in 1973. But by then, stagnation and a bitterly cynical dissident movement had set in in a paranoid Soviet Union, and the renewed arms race against the Evil Empire under US president Ronald Reagan was enough to push it into "the ash heap of history", as Reagan was so fond of saying.

Oh, I almost forgot Mikhail Gorbachev (1990), Time’s "Man of the decade", who naively thought he  could reinvent détente and share his goodwill with the most hawkish western leaders of the postwar period, and who mistook western flattery and subversion for disinterested friendship. What can I say? For Gorby, the award was more like a consolation prize for losing the Cold War. He made no acceptance speech and within 6 months he would ousted from power and his Communist Party outlawed. The only other communist to be awarded the prize -- Le Duc Tho -- had wisely refused it, considering the fate of his comrade.

could reinvent détente and share his goodwill with the most hawkish western leaders of the postwar period, and who mistook western flattery and subversion for disinterested friendship. What can I say? For Gorby, the award was more like a consolation prize for losing the Cold War. He made no acceptance speech and within 6 months he would ousted from power and his Communist Party outlawed. The only other communist to be awarded the prize -- Le Duc Tho -- had wisely refused it, considering the fate of his comrade.

What has taken the place of the vision of peace-through-detente, as Orr, Pauling and Brandt fought for? The post-Soviet world is shaping up as one of permanent war, with the people of the former Soviet Union reduced to misery, the precious test ban treaty and virtually every other disarmament treaty looking more and more like waste paper, echoing Orr's warning that the road to peace through disarmament treaties is "a vain hope". Now that the Soviet Union is safety defunct, Orr’s plea that "the Western countries give full credit to what the USSR has done against appalling difficulties, including the hostility of capitalist countries" is finding a voice, as mainstream historians are waking up to the fact that "the Cold War as a struggle to the death between Good (Britain and America) and Evil (the Soviet Union) was seriously mistaken," that "it was one of the most unnecessary conflicts of all time, and certainly the most perilous.” [Andrew Alexander, Spectator, 27/4/02]

Of course, no amount of Nobel prizes to détente enthusiasts could have tipped the scales of history. And then there are the positive developments in Nobel Peace Prizes in the postwar period -- the emphasis on human rights (though the award to Sakharov and Liu Xiaobo (2010) make it clear that these are  'human rights' as defined by capitalism), the less white, male, Euro-American focus of the awards, the recognition that the struggle for peace requires a global economic (Muhammad Yunus, 2006) and environmental (Al Gore, 2007) perspective.

'human rights' as defined by capitalism), the less white, male, Euro-American focus of the awards, the recognition that the struggle for peace requires a global economic (Muhammad Yunus, 2006) and environmental (Al Gore, 2007) perspective.

We need only note that George Bush, Tony Blair and Hamid Karzai were on the shortlist for 2002 for their invasion of Afghanistan, and that yet another US president, Barak Obama, of dubious qualifications actually won the award in 2009 (albeit for his  qualified opposition to further such adventures), to see that the Nobel's rejection of 'might makes right' is still being ignored. President Carter’s award (2002) for his many good deeds since he was pushed aside by a warmongering Reagan ignore his many sins as president -- organizing death squads in Argentina to train Nicaraguan Contras, propping up vicious military dictatorships in El Salvador, South Korea and Indonesia, and as piece de resistance, authorizing covert CIA operations in Afghanistan that led to the rise of Osama bin Laden.

qualified opposition to further such adventures), to see that the Nobel's rejection of 'might makes right' is still being ignored. President Carter’s award (2002) for his many good deeds since he was pushed aside by a warmongering Reagan ignore his many sins as president -- organizing death squads in Argentina to train Nicaraguan Contras, propping up vicious military dictatorships in El Salvador, South Korea and Indonesia, and as piece de resistance, authorizing covert CIA operations in Afghanistan that led to the rise of Osama bin Laden.

The trio of laureates in 2011 (Liberia's Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, Africa's first freely elected female head of state, Leymah Gbowee, who led a "sex strike" to help end Liberia's civil war, and Yemeni activist Tawakul Karman) follow only a dozen other women among 85 men, as well as the  handful of organisations, to have won the prize over its 110-year history. This is a modest success story for the prize today. However, the 2012 award to the EU for "the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe" was a step back to the anti-communism underlying the Peace Prize, considering the shameful role the EU played in the dismantling of Yugoslavia and its kowtowing to the US/Israel over sanctions to Iran. And the 2013 prize to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW, Director General Ahmet Uzumcu), that led the way to a process for the destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons, again honors an organization (the real winners were Putin, Obama, and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad). The OPCW has been implementing the Chemical Weapons Convention (1997), which still does not include North Korea, Angola, Egypt and South Sudan (Israel and Myanmar have signed but not ratified the convention). Afghan Malala Yousafzai became the youngest Nobel winner ever as she and Kailash Satyarthi of India won the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize for working to stop child slavery. The 2015 Nobel Peace Prize went to the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet “for its decisive contribution to the building of a pluralistic democracy in Tunisia in the wake of the Jasmine Revolution of 2011. In 2016, in what looked like a Nobel faux pas, President Juan Manuel Santos was awarded the prize for the negotiations that have sought to end the 50-year conflict in Colombia (ignoring FARC rebel leader Rodrigo Londoño), but which failed to be ratified in a referendum. The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, a coalition of 468 organizations in 101 countries launched in 2007, received the 2017 award "for its work to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and for its ground-breaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition of such weapons". Denis Mukwege, a gynaecologist treating victims of sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Nadia Murad, a Yazidi human rights activist and survivor of sexual slavery by Islamic State in Iraq, won the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to end the us of sexual violence as a weapon of war. The 2019 prize was awarded to Abiy Ahmed Ali "for his efforts to achieve peace and international cooperation, and in particular for his decisive initiative to resolve the border conflict with neighbouring Eritrea." The 2020 prize, in a subtle jab at Trump's use of boycotting his enemy du jour (Iran, Yemen), to the World Food Program, "for its efforts to combat hunger, for its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict," established in 1961, following calls from Eisenhower. the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize went to Dmitry Muratov, the editor-in-chief of the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta, and Filipino journalist Maria Ressa, "for their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace" (i.e., for standing up to their respective autocratic presidents. oh yes, and Anna Politkovskaya, murdered on Putin's birthday, was journalist at Novaya Gazeta.). The 2022 prizes blatantly anti-Russia-Belarus, pro-Ukraine (so much for peace :(-- human rights advocate Ales Bialiatski from Belarus, the Russian human rights organisation Memorial and the Ukrainian human rights organisation Center for Civil Liberties. Given the last three awards went to the 'collective West's' agents to undermine Russia, predictably the 2023 went to the other endless campaign to undermine Iran. Yes, 51-year-old Iranian journalist and activist Nages Mohammadi has spent much of the past two decades in and out of jail for her campaign against the mandatory hijab for women and the death penalty. Death penalty, definitely bad. Hijab?

handful of organisations, to have won the prize over its 110-year history. This is a modest success story for the prize today. However, the 2012 award to the EU for "the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe" was a step back to the anti-communism underlying the Peace Prize, considering the shameful role the EU played in the dismantling of Yugoslavia and its kowtowing to the US/Israel over sanctions to Iran. And the 2013 prize to the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW, Director General Ahmet Uzumcu), that led the way to a process for the destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons, again honors an organization (the real winners were Putin, Obama, and Syrian President Bashar al-Assad). The OPCW has been implementing the Chemical Weapons Convention (1997), which still does not include North Korea, Angola, Egypt and South Sudan (Israel and Myanmar have signed but not ratified the convention). Afghan Malala Yousafzai became the youngest Nobel winner ever as she and Kailash Satyarthi of India won the 2014 Nobel Peace Prize for working to stop child slavery. The 2015 Nobel Peace Prize went to the Tunisian National Dialogue Quartet “for its decisive contribution to the building of a pluralistic democracy in Tunisia in the wake of the Jasmine Revolution of 2011. In 2016, in what looked like a Nobel faux pas, President Juan Manuel Santos was awarded the prize for the negotiations that have sought to end the 50-year conflict in Colombia (ignoring FARC rebel leader Rodrigo Londoño), but which failed to be ratified in a referendum. The International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, a coalition of 468 organizations in 101 countries launched in 2007, received the 2017 award "for its work to draw attention to the catastrophic humanitarian consequences of any use of nuclear weapons and for its ground-breaking efforts to achieve a treaty-based prohibition of such weapons". Denis Mukwege, a gynaecologist treating victims of sexual violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Nadia Murad, a Yazidi human rights activist and survivor of sexual slavery by Islamic State in Iraq, won the 2018 Nobel Peace Prize for their efforts to end the us of sexual violence as a weapon of war. The 2019 prize was awarded to Abiy Ahmed Ali "for his efforts to achieve peace and international cooperation, and in particular for his decisive initiative to resolve the border conflict with neighbouring Eritrea." The 2020 prize, in a subtle jab at Trump's use of boycotting his enemy du jour (Iran, Yemen), to the World Food Program, "for its efforts to combat hunger, for its contribution to bettering conditions for peace in conflict-affected areas and for acting as a driving force in efforts to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict," established in 1961, following calls from Eisenhower. the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize went to Dmitry Muratov, the editor-in-chief of the Russian newspaper Novaya Gazeta, and Filipino journalist Maria Ressa, "for their efforts to safeguard freedom of expression, which is a precondition for democracy and lasting peace" (i.e., for standing up to their respective autocratic presidents. oh yes, and Anna Politkovskaya, murdered on Putin's birthday, was journalist at Novaya Gazeta.). The 2022 prizes blatantly anti-Russia-Belarus, pro-Ukraine (so much for peace :(-- human rights advocate Ales Bialiatski from Belarus, the Russian human rights organisation Memorial and the Ukrainian human rights organisation Center for Civil Liberties. Given the last three awards went to the 'collective West's' agents to undermine Russia, predictably the 2023 went to the other endless campaign to undermine Iran. Yes, 51-year-old Iranian journalist and activist Nages Mohammadi has spent much of the past two decades in and out of jail for her campaign against the mandatory hijab for women and the death penalty. Death penalty, definitely bad. Hijab?

Parsing Nobel Peace prizes has become a fool's errand, a waste of time. Considering both Norway and Sweden were very likely involved in blowing up the Nord Stream pipeline, and both are loud newbie NATOistas, are Nobel's prize a sign of imminent collective western brain death? They stopped inspiring long ago.

--

As the Peace Prize enters its second century, it has spawned alternative awards that better reflect genuine peace activities. The Carl von Ossietzky Medal is given by the International League for Human Rights, the heir to Ossietzky's organization founded in 1914, since 1962, and includes such recipients as Gunther Grass, Heinrich Boll, Mairead Corrigan, the Palestinian Citizens Committee of the village of Bilin, Israeli Anarchists Against the Wall, and Edward Snowden.

Another Carl von Ossietzky-inspired Prize for Contemporary History and Politics was founded in 1984 and has been awarded to Uri Avneri, Noam Chomsky and Deborah Lipstadt.

The Right Livelihood Award, was established in 1980 to honor work in environmental protection, human rights, sustainable development, health, education, and peace. It is awarded in Stockholm as a complement to the Nobel prizes and as such is called the Alternate Nobel Peace Prize. By 2010, it has recognized the work of 141 individuals and organizations from 59 countries, including Egyptian architect Hasan Fathy, German Green Party activist Petra Kelly, Israeli peace activist Mordachai Vanunu, Brazil's Landless Workers' Movement, Nigeria's Movement for the Survival of the Ogoni People, and Americans Daniel Ellsberg, Amy Goodman, Gene Sharp, Snowden, Greta Thunberg and Vladimir Slivyak co-chair of the Russian environmental NGO Ecodefense.

US whistleblower and international hero Bradley Manning was awarded the 2013 Sean MacBride Peace Award by the International Peace Bureau, itself a former recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize (1910), for which Manning is a nominee this year. Also Chomsky, Jeremy Corbyn and Black Lives Matter.

Julian Assange, Snowden and Manning all were awarded the Sam Adams Award, founded by former CIA official Ray McGovern, given to an intelligence professional who has taken a stand for integrity and ethics. Assange has been given 20 awards since 2008, including Time Person of the Year, Reader's Choice (2010).

http://www.peacemagazine.org/ (2002, revised 2012, 2013, 2016, 2021)